د. سالم الاكحل، أستاذ جامعي

مهنة الصحافة والإعلام من الناحية النظرية تعد عين، وعقل، وضمير المواطن والوطن، ومن المفروض انها أداة الشعب لمراقبة جميع سلطات ومؤسسات الدولة وفضح الفساد ان وجد، ومن المفروض تلقي الضوء على الحسنات والسيئات، ومواضع الضعف، وأماكن القوة، ومشاهد القبح وصور الجمال، وهي في الوقت نفسه همزة الوصل بين النظام الحاكم والمواطن، هي أداته ونافذته لتشكيل الرأي العام في القضايا القومية والمصيرية، ونافذته لمخاطبة المواطنين وتعريفهم بالقرارات والسياسات والقوانين وغيرها.

وكذلك أيضا من الناحية النظرية الإعلام يُسهِم في تشكيل أفكار الأمَّة، وهذا التشكيل إمَّا أن يكون عاملَ بِناء يَحثُّ الأمةَ على التقدُّم والتنمية والتماسُك، وإمَّا أن يكون عاملَ هدْم يُحدِث اضطرابًا وقلَقًا فكريًّا واعتقاديًّا، بل واجتماعيًّا.

زيادة على ذلك نظرياَ، الإعلام النزيه المِهني هدَفُه عرض امين للقضايا، ويَقِف على مسافة واحدة مع جميع الأطراف التي يتعاملُ معها؛ فلا يُجامِل طرفًا على حساب الآخر، ولا يَتحامَل عليه؛ لأنَّ كلَّ هَمِّه الوصول إلى الحقيقة، فليس همُّه إحداثَ السَّبق الصحفي، ولا هدَفُه تشويه فَصيل يَختلِف معه في الرُّؤى، ولا يَستخدِم إعلامه من أجل تحقيق مَآرب شخصيَّة أو مؤسَّسيَّة. الهدف يبقى طرح المواضيعَ مهما كانت نوعها سياسية او اجتماعية أو علميّة أو ثقافية بشكل هادف وجدي، والتي من شأنها أن تجذب الناس وخاصة الشباب وتحفّزهم للتأمل في معاني المسؤولية والمبادرة والإبداع والابتكار والهدف يبقى خدمة المجتمع والنهوض به.

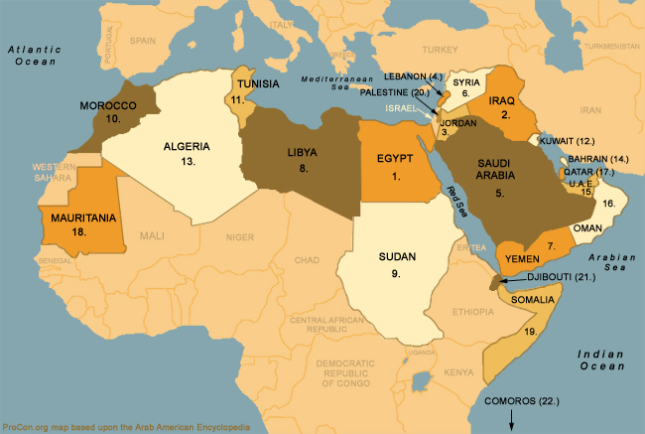

لنقيس الآن واقع الإعلام العربي بكافة أشكاله المرئي والمسموع والمقروء، بما فيه العالم الافتراضي على المثال النضري الذي سبق ذكره. وبما انه تشخيص اي مرض او علة يبدا بالسؤال والتساؤل، فيما يلي بعض الأسئلة التي يمكن ان تساعدنا على ذلك.

مهنة الصحافة والإعلام من الناحية النظرية تعد عين، وعقل، وضمير المواطن والوطن، ومن المفروض انها أداة الشعب لمراقبة جميع سلطات ومؤسسات الدولة وفضح الفساد ان وجد، ومن المفروض تلقي الضوء على الحسنات والسيئات، ومواضع الضعف، وأماكن القوة، ومشاهد القبح وصور الجمال، وهي في الوقت نفسه همزة الوصل بين النظام الحاكم والمواطن، هي أداته ونافذته لتشكيل الرأي العام في القضايا القومية والمصيرية، ونافذته لمخاطبة المواطنين وتعريفهم بالقرارات والسياسات والقوانين وغيرها.

أسئلة الإجابة عنها يمكن تقربنا من تشخيص العلة

هل الاعلام مقيد؟

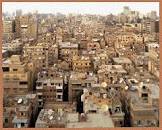

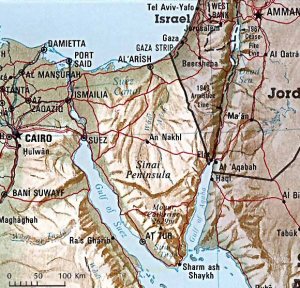

تقييد الاعلام أداة لأعماء الشعب، وجره بدون بصر أو بصيرة. وتستخدم السلطات آليات متنوعة حسب الحالة التي تتناولها، منها قطع الإعلانات التجارية عن الصحف المعنية وحملات التشهير بها بل واللجوء الى القضاء، وذلك في ظل إعادة إدخال الجنح الصحافية الى القانون الجزائي. فاذا كان الاعلام مقيد فان الخوف والمراقبة الذاتية تلجم الصحافيين عن التطرق للمشاكل الحقيقية للامة خوف من التهم التي تكون جاهزة. ففي مصر مثلا كل شخص ينتقد النظام او يعمل مراسل لقناة معارضة (كقناة الشرق او مكملين او الجزيرة …) او يظهر على شاشتها يتهم بالتخابر ونشر أخبار كاذبة تضر بالأمن القومي. أن الأمر “تعدى الاعتقال بغرض الترهيب، فقد بلغ ما هو أخطر، كما جرى مع السياسي ايمن نور، صاحب قناة الشرق، بهدم مركزه الثقافي، والكاتب سليمان الحكيم، بهدم منزله كما تروي الجزيرة (الجزيرة 2017) لضهورهم في قنوات المعارضة.

هل الاعلام يعتذر عند الخطء؟

مثل أي مهنة تجمع الصحافة والإعلام مختلف النوعيات من البشر، السيئ والجيد، الشريف والفاسد، كما أنها غير مبرأة من الخطأ، أغلب العاملين في مهنة الصحافة والإعلام يقعون في أخطاء كبيرة وصغيرة ومتوسطة، متعمدة او غير متعمدة؛ او لفساد أو لجهل من الصحافي والإعلامي. الاخطاء المتعمدة قرينة على الفساد ولا يتبعها عادة أي اعتذار. اما الأخطاء الغير المتعمدة إذا تبعها اعتذار فيكون عادة مقبول ويدل عادة على نزاهة الصحافي او الوسيلة الإعلامية.

هل الاعلام يثير الفتن؟

الإعلامي الفاسد هو الذي يثير الفتن والمشكلات بين اطياف المجتمع داخل الدولة اوبين الدول. والإعلامي الفاسد هو الذي يحمل رسائل من هذا النوع تُجْهز على كل ما من شأنه التقريب بين الدول والشعوب والأفراد داخل أي مجتمع.

فاذا رأيت إعلاميًا يتكسب بصوته على حساب استقرار دولته ومجتمعه من أجل مصالح شخصية بحتة تتاح إما من خلال التربح لمن يدفع أكثر، أو على أساس استغفال الجماهير المغيبة بنشر اخبار غير صحيحة فذلك قرينة بانه فاسد.

فاذا رأيت اعلاما يحاول باستمرار أن يعتم على مناطق الالتقاء والمصالح الممكنة بين الدول العربية بصفة عامة او الدول الإقليمية كدول المغرب العربي او دول مجلس التعاون الخليجي، فهذه هي قرينة على الفساد. الاعلام الفاسد يحاول ان يلعب على المواضيع الخلافية كموضوع النقاب والحجاب والشيعة والسنة والجهوات داخل الدولة الواحدة وكذلك بين الدول مثل ما وقع على إثر مباراة كرة القدم بين الامرات وقطر والتي فازت بها قطر 4-0 في نطاق كاس اسيا للأمم لسنة 2019. فنتيجة ذلك كان استقطاب الاعلام المصري والسعودي والإماراتي من جهة واعلام دول العربية من جهة اخرى.

هل الاعلام والإعلاميين يغيرون مواقفهم من نفس القضية حسب الزمان والمكان؟

إذا اخذنا مثلا قضية حقوق الانسان، من المفروظ ان انتهاك هذه الحقوق ممنوع في كل الدول وليس في الدول المتقدمة فقط. هذا المنطق السليم لا ينخرط فيه معظم ولاة أمور الدول العربية. على سبيل المثال لا الحصر رئيس مصر السيسي المنقلب على السلطة الشرعية في الندوة الصحفية التي جمعته بالرئيس الفرنسي ماكرون في اخر شهر جانفي-يناير 2019 في القاهرة، لما انتقد ماكرون حقوق الانسان المتدهورة خلال حكم السيسي رد السيسي: اننا لسنا في اوروبا او في أمريكا لنحترم حقوق الانسان.

المثال الثاني هو الموقف من الاستبداد وطول الحكم لحكام مفلسين وفاسدين، من المفروض ان يكون الموقف من الظاهرة ثابت وموحد ولا يتغير حسب الزمان والمكان. فاذا رأينا المواقف تتغير لارتباطات ومصالح سابقة أو منافع منتظرة فيكون ذلك قرينة على الفساد. في هذا الصدد اظهر الصحافي محمد كريشان (2019) في القدس العربي الازدواجية عند بعض الصحافيين آخذا في ذلك مثال صحفيان عربيان معروفان، يقيمان في أوروبا منذ سنوات دون تسميتهم.

“هؤلاء الصحافيان يعرفان تماما نعمة الحرية وحلاوة التداول السلمي

على السلطة، الأول كان متعاطف مع احتجاجات السودان ضد الرئيس البشير الذي له في

السلطة أكثر من ثلاثين سنة فنعته ب «قاتل الأطفال في اليمن» بحكم مشاركته في حرب

«التحالف العربي». لكن هذا الصحافي نفسه يدافع عن بشار الأسد ولم يدن أبداً قتله لشعبه

وتشريده بما فيهم الأطفال بل هو سعيد حاليا بـ«النصر» الذي حققه على «المؤامرة

الكونية» ضد حكمه «الممانع»، كما أنه كان قبل ذلك متعاطف مع الراحل علي عبد الله

صالح وما كان يرى في الثورة عليه أي مبرر رغم أنه يشترك مع البشير في أسلوب حكمه

وطول سنواته. الصحافي الثاني كان مصفقا لكل ثورة حتى إذا ما وصلت السودان انبرى

مدافعا عن البشير بضراوة داعيا السودانيين إلى التعقل حتى لا يحل بهم ما حل بتونس

الذي كان هو مزهواً وقتها برحيل بن علي عنها”!!

هذه النماذج ليست الوحيدة ومن المفترض أن يكون الصحفي صاحب مبدئ ومنصف ويقف مع قيم

الحرية ويدين كل من يعرقل مسيرتها، يدافع كذلك عن هبات الشعوب ضد الاستبداد والمطالبة

بالديمقراطية وكسر “سطوة أجهزة الأمن والمخابرات على كل مفاصل الدولة”.

ولكن ما الذي حصل للكثير من بيننا:

“هذا هلل لما حدث في تونس ومصر حتى إذا وصل إلى ليبيا صرخ وقال انظر إلى

«الناتو» وما يفعله هناك متجاهلاً ما كان يفعله القذافي، ثم واصل سيره مؤيداً ما

حدث في البحرين واليمن!!

هذا أيد ثورة تونس فمصر فليبيا فاليمن فالبحرين حتى إذا ما اندلعت الاحتجاجات في

سوريا صرخ «مؤامرة» ضد «محور الممانعة»!!

هذا وقف مع كل الثورات حتى إذا تحرك البحرينيون قال «شيعة تدعمهم إيران»!!.

هذا الذي وقف مع بشار لا يجد حرجا في تقريع من تخاذل في دعم البحرينيين!!

هناك أيضا من ساند كل الثورات حتى إذا وصلت السودان اعتبرها «ثورة مضادة»!!

هناك أيضا من كان ينتقد «الربيع العربي» ويرى فيه شراً مطلقاً بلا جدال ولكن عندما

تحرك السودانيون رأى من الواجب مساندتهم في احتجاجاتهم”!

هل الاعلام يهتم بالأحداث السلبية فقط؟

هل من المنطق ان يركز الإعلام على الكوارث وعلى ما يعاني منه المواطن من مشاكل فقط. في حالة الاستقطاب السياسي تجد وسائل الاعلام تنحاز عن مهمتها الاصلية الا وهي الاعلام النزيه وعدم الانحياز لدعم توجهات بعينها. ونجد من يحاول وضع الأخبار في أطر تقلل من أهمية الأحداث ونتائجها، او تضخيم الاحداث لجعل الانسان يشعر بالخوف وعدم الأمان لخدمة جهة معينة. فهذا التصرف يكون قرينة فساد. لتوضيح هذا الفكرة لنأخذ مثلا تعامل وسائل الاعلام زمن تهاطل الثلوج في بعض مناطق تونس بعد الثورة زمن حكم الترويكا والتي كانت متكونة من حركة النهضة والمؤتمر من أجل الجمهورية والتكتل الديمقراطي من أجل العمل والحريات. في ذلك الوقت كانت الدولة العميقة تحاول ان تفشل الثورة والاتجاه الديمقراطي الذي اخذته البلاد.

الترويكا بدأت الحكم بعد انتخابات نزيهة بداية 2012. مع بداية تلك الفترة تساقطت الثلوج بكميات كبيرة على مدن تونسية عدة.

وفي سنة 2015 في نفس الفطرة صار الحكم في يد حزب نداء تونس ورئيسه الباجي قايد السبسي رئيسا للبلاد ونزلت كذلك كمية من الثلوج في نفس الأماكن والمرتفعات. فبالرغم من المشاكل التي انجرت على نزول الثلج كانت متشابهة من حيث انقطاع التيار الكهربائي وتعطيل الطرقات وعزل بعض المناطق، فكانت ازدواجية تعامل وسائل الإعلام الرسمي مع هذه الأزمة بائنة لكل ذي بصيرة كما يدل مقطع فيديو من نحو ثماني دقائق تداوله ناشطون، تمت مقارنة ما قدمه التلفزيون الرسمي التونسي خلال سنة 2012 وسنة 2015 .

فخلال بداية فترة حكم الترويكا تم التركيز عبر التقارير التلفزيونية على التأثيرات السلبية لتساقط الثلوج، والتأكيد على أنها ساهمت في عزل المدن وقطع الطرق وشلّ حياة المواطنين الذين يشكون من الفقر والخصاصة. واظهرت مواطنين بمدينة عين دراهم بانتظار تسلم المعونات خلال فيفري / فبراير 2012. في المقابل فإن الإعلام الرسمي تعامل مع هذه الثلوج التي نزلت في نفس الفترة من سنة 2015 على أنها تساهم في تنشيط الحركة السياحية في مدينة عين دراهم التابعة لولاية جندوبة بشمال غرب تونس، وكانت كل الآراء تعبر عن فرحة بالمشاهد الجميلة في المدينة الجبلية. هذا التناقض المفضوح لم يمر بسلام فقام عدد من المعلقين بتعريته وابرازه على ان التغطية للتي قامت وسائل الإعلام تثبت تباينا واضحا، مشيرين إلى أن الإعلام لم يتعامل بموضوعية مع حدث واحد.

حسب قناة الجزيرة (الجزيرة 2015) التي تابعت القضية في وقتها قالت في هذا الموضوع بان الصحفي التونسي كمال الشارني في تدوينه على فيسبوك “ليس إعلام العار، إنما إعلام التقصير، في هذا الوضع الصعب في غرب البلاد، الناس تكاد تموت من البرد بسبب الفقر والحاجة ونقص الخدمات العمومية وانهيار البنية التحتية، والإعلام العمومي غارق منذ الصباح في الصور المتحركة ثم المسلسلات التركية أو التونسية القديمة الغارقة في سخافات. وعلى صعيد مواز نشر ناشطون صورا تقارن بين تعامل الحكومة الحالية ورئاسة الجمهورية مع الأزمة. حيث تشير هذه الصور إلى تنقل الرئيس التونسي السابق منصف المرزوقي سنة 2012 إلى المناطق المتضررة جراء تساقط الثلوج والأمطار، وإلى عدم قيام الرئيس الباجي قايد السبسي سنة 2015 بزيارات مماثلة.

ذلك الحدث اظهر الاعلام التونسي، في تلك الفترة، بان وظيفته ليست الاعلام النزيه والتثقيف والتوعية، وأن المشاهد ليس له الحق في المعرفة، وان هذا الإعلام منحاز لجهة محددة ويلعب دورا في خلق راي عام مغاير للواقع. كما أنه لم يكن صوتًا لمن ليس لهم صوت وانما كان أداة في يد جهة معينة محسوبة على الثورة المضادة. مع العلم انه من المستحيل في عصر تعددت فيه مصادر المعلومات والمعرفة أن تحجب الحقيقة عن المواطن.

هل الوسيلة الإعلامية لها ميثاق شرف يمكن الاطلاع عليه؟

الإعلام جزء من حياة

الناس كما بينا سابقا فهو يلعب دورًا كبيرًا وخطيرًا في معرفة الحقائق وتوظيفها

ويلعب نفس الدور في تزييف الحقائق، ويكون ذلك عندما تنعدم الضوابط والأخلاقيات ولا

يكون هناك ميثاق شرف إعلامي او رادع قانوني. في هذه الحالة يمكن تغيب الحقيقة، فيظهر

الحق على أنه باطل ويظهر الباطل على أنه حق، وتضخ في سبيل ذلك الاموال خلال آلة

إعلامية جبارة تعمل ليل نهار بدون رادع. فان وجد هذا الميثاق ويمكن الاطلاع عليه

من العموم يكون قرينة على مهنية وموضوعية وحيادية وسيلة الاعلام. هناك دائما حدود وقيود

وخطوط حمراء لا يجوز تخطيها وكيفية التعاطي مع الضيوف وإدارة الحوارات والتأكد من

مصادر الاخبار قبل اذاعتها او تبنيها كل هذه التصرفات تكون واضحة في ميثاق الشرف.

الهيئات الرقابية للإعلام التي نجدها في بعض الدول مثل تونس لها وضيفة زجرية

وعقابية ويمكن ان تصدر احكام إذا وقع التعدي عل الخطوط والمبادئ العامة

للمهنة. ولكن من الافضل ان تجعل كل وسيلة

اعلام لنفسها ميثاق شرف يذهب في التفاصيل أكثر مما تطلبه الهيئة الرقابية.

على سبيل المثال ميثاق الشرف لقناة الجزيرة الإخبارية يعتمد على عشرة مبادئ (خنفر 200

أولا التمسك بالقيم الصحفية من صدق وجرأة وإنصاف وتوازن واستقلالية ومصداقية وتنوع دون تغليب للاعتبارات التجارية أو السياسية على المهنية،

ثانيا السعي للوصول إلى الحقيقة وإعلانها في التقارير والبرامج والنشرات الإخبارية بشكل لا غموض فيه ولا ارتياب في صحته أو دقته،

ثالثا معاملة الجمهور بما يستحقه من احترام والتعامل مع كل قضية أو خبر بالاهتمام المناسب لتقديم صورة واضحة واقعية ودقيقة مع مراعاة مشاعر ضحايا الجريمة والحروب والاضطهاد والكوارث وأحاسيس ذويهم والمشاهدين واحترام خصوصيات الأفراد والذوق العام،

رابعا الترحيب بالمنافسة النزيهة الصادقة دون السماح لها بالنيل من مستويات الأداء حتى لا يصبح السبق الصحفي هدفا بحد ذاته،

خامسا تقديم وجهات النظر والآراء المختلفة دون محاباة أو انحياز لأي منها،

سادسا التعامل الموضوعي مع التنوع الذي يميز المجتمعات البشرية بكل ما فيها من أعراق وثقافات،

سابعا الاعتراف بالخطأ فور وقوعه والمبادرة إلى تصحيحه وتفادي تكراره،

ثامنا مراعاة الشفافية في التعامل مع الأخبار ومصادرها والالتزام بالممارسات الدولية المرعية فيما يتعلق بحقوق المصادر،

تاسعا التمييز بين مادة الخبر والتحليل والتعليق لتجنب الوقوع في فخ الدعاية والتكهن،

عاشرا وأخيرا الوقوف إلى جانب الزملاء في المهنة وتقديم الدعم لهم عند الضرورة

قدمنا في هذه الورقة بعض الاسئلة التي يمكن طرحها للوقوف على مدى التزييف والتشويه الإعلامي الذي يمكن ان نتعرض له. فعلى المتلقي ان يكون قادرا على تقييم المادة الإعلامية التي تقدم له، لان الفاسدين يكنون ضالعين في توصيل المعلومة للناس بصورة براقة على غير حقيقتها في الأصل، ويستخدمون جميع الطرق لتضليل الناس. فعلى سبيل المثال يمكن توجيه الأخبار سواء في المعالجة أو منع النشر لبعض الأخبار الهامة حتى تفقد قيمتها الحقيقة مقابل أخبار تافهة من المفروض ان لا يكون لها حظ من النشر.

لا يجب ان نكون ساذجين، إن أغلب وسائل الإعلام التي

من حولنا موجهة في الأساس إما لخدمة قيم وسلوكيات وإما موجهة ضد قيم مجتمعية، أو

يوظفها أصحابها لخدمة مصالحهم الشخصية والمالية او جهة او حزب سياسي معين. فعلى

المتلقي ان يبذل جهدا للوقوف على وسائل إعلامية تتحرى الحياد في تغطيتها فلا تميل

لجانب دون جانب ولا تنحاز لفكرة دون أخرى.

هذا المجهود ليس بهين

ويتطلب قسطا من الوعي والذكاء للتمييز لكيلا نقع ضحية هذه الوسائل الإعلامية التي

يمكن ان تكون مقترنة بالفساد.

ان أحسن عقاب يمكن ان يسلط على وسيلة الاعلام هو فضحها وهجرها. أي وسيلة اعلام تعيش من مشاهديها او مستمعيها او قرائها او متابعيها. فاذا تبين فسادها فهجرها يصبح ضرورة وبفضل وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي يمكن للجميع ان يعبر عن رايه وينسق حملة ضد الذي يظهر فساده. وإذا فقدت وسيلة الاعلام جمهورها يكون موتها محقق. اما الإجراءات القانونية تتطلب وقت واموال للتقاضي ويمكن لوسيلة الاعلام ان تستغلها لصالحها لتبدو بمظهر الضحية وتجلب العطف.

هوامش

الجزيرة (2015). الثلوج بتونس تفضح ازدواجية الإعلام بين الترويكا والسبسي. تقارير وحوارات. الأخبار, Aljazeera.

الجزيرة (2017) اعتقال الضيوف بعد الصحفيين بمصر لإسكات فضائيات الخارج.

خنفر, و. (2004). مواثيق الشرف الإعلامية. من واشنطن. ح. الميرازي, قناة الجزيرة.

كريشان, م. (2019). تناقضات الحيران من تونس إلى السودان. القدس العربي. لندن.